Earlier this year, I've posted an article about a mysterious case of attorney discipline in South Carolina that originated in federal courts, involved hidden court dockets and made no sense whatsoever from the text of the disciplinary decision.

In that blog, I pointed out that a member of the public cannot figure out from the disciplinary decision, what cases are involved, and the official registry of federal court cases do give any clue in that matter.

Since then, I received a tip from a reader, pointing me to the right cases. I obtained some, but not all docket reports about the underlying federal case in question, and so many "irregularities" surfaced in the case that it made my head spin.

An attorney was disciplined based on that case by the South Carolina Supreme Court.

Attorney regulation, and discipline, exists - at least, the government and legal establishment declares that it is the main purpose of attorney regulation - to protect consumers from incompetent or unscrupulous attorneys.

But, as I read through the documents in the case that the tip pointed me to, I realized more and more that the public was protected from the wrong person, and that the people who the public needs to protect from are those who prevented proper enforcement of federal law, hid court dockets (an unconstitutional practice, see a similar scandal emerging in New York courts at this time) and punished not only an attorney for his diligent work, but also a party for following the law.

This case deserves diligent deciphering - and I will try to do that.

First of all, it helps to understand who the actors are.

Here is the original complaint, filed in the U.S. District Court in the Middle District of Georgia before judge Clay D. Land (a "CDL" designation in the civil action number on the right).

Note that Judge Clay Land, after transferring this case to South Carolina federal court - a move that decided the fate of the case and the fate of attorney Nolan, in favor of a South Carolina corporation despite recorded evidence of its infringement of intellectual property rights of two Georgia corporations, including a corporation called "University of Georgia Research Foundation" - was elevated to the position of Chief Judge of that federal court.

Let's also note that the attorney for defendants was a Robert Fredrick Goings of Columbia SC, of the Goings Law Firm, see trial docket report:

The Goings Law Firm advertises results of its work - with the required disclaimer at the bottom of the long list of achievements, that the firm does not guarantee those results.

As one of the top results on the list it lists this: "successful defense verdict in a multi-week intellectual property and infringement trial in the Federal District Court of South Carolina. Prevented a $4.2 million dollar verdict.

Boy did Robert Fredrick Goings prevent that, and then some. After all, attorney Robert Fredrick Goings, by his own admission, "has a knack for winning big verdicts".

Here is also one more interesting document filed by attorney Robert Fredrick Goings with the South Carolina STATE Supreme Court

In this masterpiece, attorney Robert F. Goings who "has a knack for winning big verdicts", as of January 13, 2014, when the appeal was still pending, attorney Robert F. Goings complains to an entity where an attorney is not licensed, about a case in a federal court governed by federal law and under the jurisdiction of attorney regulation by the federal bar.

I wonder why attorney Robert F. Goings did not file his complaint where he was supposed to.

But, anyway, Robert F. Goings admits in his complaint that

- the attorney he is complaining about is an "out of state attorney"

Actually, attorney Goings likely made a false statement in that complaint claiming that

"Mr. Nolan was admitted pro hac vice to practice in South Carolina in the /sic/ a civil action captioned The Turfgrass Group, Inc. and the University of Georgia Research Foundation, Inc. v. Carolina Fresh Farms, LLC, Civil Action No. 5:10-cv-00849-JMC".

Watch the careful sleight of hands by attorney Robert Goings:

- he misrepresents to the South Carolina Supreme Court that attorney Duff Nolan was actually admitted pro hac vice to practice IN SOUTH CAROLINA - that had to be admission by the SC Supreme Court to practice in state courts of South Carolina; then

- he carefully omits the name of the court in claiming that after being admitted "pro hac vice to practice IN South Carolina", Mr. Nolan actually practice "in South Carolina", in a "civil action No. 5:10-cv-00849-JMC".

The problem with the last statement though is, as the docket indicates, and Robert Goings own "motion for sanctions" attached to the complaint confirms, that the case was litigated not "in South Carolina" - not in South Carolina State Courts - but in a federal court:

- so, the governing disciplinary authority over attorney Duff Nolan, an attorney who IS admitted pro hac vice in FEDERAL court within the territory of South Carolina, but IS NOT admitted by the State Supreme Court of South Carolina, and the case thus DOES NOT invoke South Carolina STATE attorney ethical rules - would have been

- the disciplinary committee of the U.S. District Court for the District of South Carolina, where the case was litigated;

- the U.S. District Court of the State of Georgia (where the case was filed originally), or

- the Arkansas State Supreme Court where attorney Nolan is licensed originally.

But, attorney Goings obviously understood that it would have been a waste of time to file a complaint there, because attorney Nolan did not violate any laws or ethical rules in Arkansas, or in federal courts.

Moreover, attorney Goings was not very forthcoming in the State Supreme Court of South Carolina either, because he also omitted to mention that sanctions he requested against attorney Nolan in federal court were denied on May 3, 2011, 3.5 years before he filed his complaint with South Carolina Supreme Court.

Attorney Goings' client did not appeal denial of sanctions against attorney Nolan, but such a denial had a collateral estoppel effect upon the South Carolina Supreme Court, barring it from imposing sanctions upon an attorney where the original federal court did not impose any discipline.

After all, what attorney Goings asked the South Carolina STATE Supreme Court to impose upon Attorney Nolan (who was not at the time admitted in South Carolina STATE Supreme Court, and the action attorney Goings was complaining about was not from the South Carolina State Supreme Court) was the so-called "reciprocal discipline" which could only be imposed if the federal court imposed discipline upon attorney Nolan - which did not happen.

The sanctions were in the nature of an order "in limine" (excluding evidence), and I will discuss legality of that order later in this article.

The federal court case was governed by federal law, in terms of procedural law and substantive law alike.

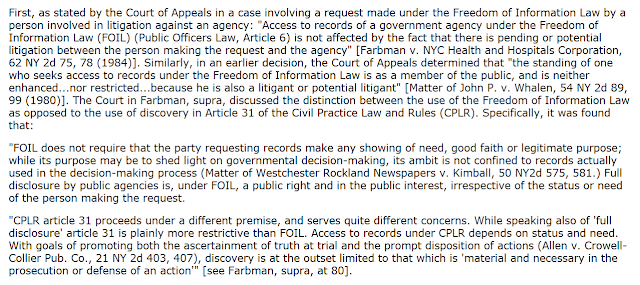

Rules of ethics of South Carolina Supreme Court had no place in that federal court proceeding where they contradicted rules of ethics accepted in such federal proceedings, and, as attorney Nolan pointed out in his response to the complaint of attorney Goings, "surreptitious recording" in preparation for an intellectual property infringement case in federal court, is an accepted practice recognized by other federal courts:

In his response to the complaint, attorney Nolan also attached an appellant's brief to the federal court, pointing out that the appeal was still pending, and described the "apple of discord" in litigation, licensing rights to market and sell the so-called "centipede grass", an apple green type of grass that does not turn brown during southern winters, but remains green, a clear attraction for golf courses that abound in southern states of the U.S.

On appeal, plaintiffs argued, among other things, the following:

Then, things got fuzzy.

There were actually two appeals in this case, as the trial docket shows, with two different docket numbers.

The first appeal was dismissed by the federal appellate court on the day of filing, in 2013.

Yet, here are some interesting details about the dates in the appellate docket.

On January 8, 2014 Attorney Nolan's clients file an Appellants' Brief in electronic format.

Within 5 days, on January 13, 2014, after obviously having received the brief (in electronic format) and being upset about it, attorney Goings HAND-DELIVERED his complaint against opposing counsel attorney Nolan:

Apparently, such a complaint, filed before the end of appellate litigation, and with the wrong disciplinary body, had a clearly discernible aim - to rattle the opposing counsel so that he would not be able to function well on appeal.

And now, to the last thing that the three courts involved in the case:

- the U.S. District Court for the District of South Carolina;

- the State Supreme Court of the State of South Carolina, and

- the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

apparently wanted to consider - the law.

Here is a table I've put together to illustrate what has happened to the plaintiffs and to their attorney Duff Nolan, even though the law was clearly on their side.

Jurisdictions

|

Statutory prohibition on surreptitious recording

of telephone conversations

with consent of only one party to the conversation

|

Rules of attorney ethics on surreptitious

recording of telephone conversations when one party to the conversation

consents

|

Rules on suppression of evidence in court based on

legal conduct

|

Was the Eerie doctrine applicable in federal court?

|

Were state ethical rule for attorneys applicable to rights of a party in federal court?

|

Are investigators allowed to put out a decoy to

catch a thief?

|

Arkansas

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

|

Yes

|

Georgia

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

|

Yes

|

Federal Courts

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No, it was a “federal question” case, federal law

was applicable; surreptitious recording was legal under the federal criminal

statute, and a decision on point in SDNY

|

|

Yes

|

ABA

|

n/a

|

No

|

n/a

|

|

|

n/a

|

South Carolina

|

No

|

Yes, in reliance on overruled ABA rule

|

No

|

|

|

Yes

|

All three states involved:

- Arkansas;

- Georgia; and

- South Carolina

So, recordings for purposes of introduction of those recordings in a federal court "federal question" case was lawful under federal law, and under the law of all three states:

- where the plaintiffs' attorney was originally from - Arkansas;

- where the case was originally filed in federal court - Georgia; and

- where the case was later litigated on transfer in federal court - South Carolina.

Since it was a "federal question" case, federal law controlled.

Under federal law it was legal.

Under the law of all 3 states it was legal.

If it was legal for the party plaintiffs to do it, it was admissible.

Had it been admitted, as attorney Goings boasts on his website, the plaintiffs could have had a verdict against them for $4.2 million - without even a jury trial, as a matter of a summary judgment.

Instead, not only the case was decided for the defendants - because of an application of South Carolina State rule of attorney ethics that, while claiming it followed the ABA rule, contradicted the modern ABA rule on the subject which was aligned with state and federal law while the South Carolina attorney ethics rule wasn't, to the work of plaintiffs' investigators which was legal under state and federal law.

Attorney Nolan attempted to explain to the South Carolina disciplinary court - as if they wanted to hear him - that, as a matter of due diligence, because of the case Twombly in federal court that required enhanced factual pleadings to survive a pre-answer motion to dismiss, he had, as a matter of due diligence, to do such investigation pre-filing.

As a matter of fact, had attorney Nolan not ordered pre-filing investigations, he could have been sanctioned for filing a meritless lawsuit without conducting a proper pre-filing investigation, based on "conclusory allegations alone" - but then, of course, defendants would have rounded up their wagons, instructed their employees and hid their evidence.

So, apparently, when you step on the wrong toe in litigation, you can be sanctioned no matter what you do.

Attorney Nolan was sanctioned because he conducted his due diligence, as required of him by attorney rules of professional conduct, as well as his duty to their client.

What I cannot get is - why federal court punished two plaintiffs, corporations, for lawful conduct, depriving them of damages for violation of their intellectual property rights?

Once again - whatever attorney Goings could be alleging that attorney Nolan could have done wrong under South Caroline State rules of ethics for attorneys, the plaintiffs and their investigators did nothing wrong under federal or state statutory law, and there was no legal basis to strike the recordings.

I wonder what kind of strings were pulled by the defendants to block clear evidence of wrongdoing, lawfully obtained by the plaintiffs, so that the jury would return a verdict for them?

Because, when clear law is not applied, it is clear that strings had to be pulled, on all levels, so that:

- Lawfully obtained evidence that had to result in a summary judgment for the plaintiffs, was blocked, and thus returned a jury verdict for the defendants (because the jury was not allowed to hear those recordings where investigators posed as customers, in a proven investigative technique of "posing a decoy to catch a thief";

- Well-respected experienced attorney for plaintiffs was sanctioned by federal court for doing his duty and following the law, and then sanctioned by a South Carolina State Supreme Court for allegedly "violating the state ethical rule" - in federal court, where what he did was legal.

All of the above so that attorney Robert Fredrick Goings could post this on his website?

But, whatever fee attorney Goings got for this case, wasn't the price for the public too high?

Because, whenever a court case is decided not on the law, but obviously based on in-state connections against out-of-state litigants and their out-of-state attorney, and especially where, like with attorney Nolan, a pretense is made that, by using connections in imposing court sanctions against a person who did nothing wrong and who diligently and lawfully worked to ENFORCE the existing law - justice is subverted.

Moreover, the University of Georgia Research Foundation, Inc., that was trying in vain to regain its rights against those who were unjustly enriching themselves by selling the product of their research, is a tax-exempt entity, operating on people's tax-exempt donations, and tax dollars.

It is the people, the taxpayers who were cheated in this case - because somebody knew the right strings to pull so that the law would stop applying.

And that's a complete shame.

I hope, this case is not at an end, and should be looked into by proper federal investigative authorities.

The should be copies of recordings still remaining for review, proving the case for the Georgia Research Foundation, and there is a deposition (marked confidential, but available for a fee online on Pacer.gov), which I have bought, together with exhibits, and am now publishing for everybody to see.

Judge for yourself how that case was decided.

It is all about pretty apple green grass that taxpayer-backed research produced - and private corporations now distribute without a license because federal court did not want to enforce federal laws.

Let's remember that.

And ask for impeachment of federal judges who blocked this license infringement case.

Here are their names and happy faces.

Judge Clay Land of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Georgia, who transferred the case from Georgia to South Carolina, and who was since elevated to the position of Chief Judge of that court.

Judge J. Michelle Childs, an "ardent ambassador" instead of a neutral applier of the law,

who went along with Robert Goings motions for sanctions and in limine and blocked lawfully obtained investigative evidence that, if allowed to be used, would have resulted in a summary judgment and a jury verdict, possibly, much exceeding the $4.2 million that attorney Robert Goings is boasting of "defending" his clients against.

And, Federal Circuit judges who affirmed the jury verdict made by a cheated jury who was not allowed to see the actual evidence in the case because of the unlawful decisions of the "ardent ambassador" District Judge J. Michelle Childs - through a "non-precedential decision", without any explanation, possibly without doing any work at all.

After all, no effort is needed to put one word "affirmed" on a piece of paper instead of engaging in legal research and reasoning, and that's what the three of them did.

Chief Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit Sharon Prost:

Federal Circuit Judge Pauline Newman, see also here (born June 20, 1927, and who was 88 years of age when she decided to endorse blocking lawfully obtained evidence without an opinion or explanation):

and

Federal Circuit Judge Richard Taranto, former law clerk of the U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor:

So - Defendants won

Attorney Goings won, and can continue advertising his winnings for this clients (without, of course, mentioning what kind of means he uses to get those winnings).

Judge Clay Land won, having been promoted to the position of Chief Judge for his transfer of the case into South Carolina, where the right connections could be pulled so that the case is decided in favor of South Carolina defendants and South Carolina attorney.

The three smiling-face judges do not care, they sit in the Federal Court of Appeals for life, and will be throwing around speeches about "judicial excellence" and the rule of law until they drop dead - while doing quite the opposite, without any explanation whatsoever.

And we, the public - lost.

Don't tell me that this is "the rule of law".

The rule of law is actually following the law, federal statutory law in this case, and not deciding a court case on a whim.

This is, ladies and gentlemen, the "rule of men" - and women - 3 women and one man actually decided this case.

We shouldn't tolerate such a rule of connections and such a perversion of justice, allowing private entities to enrich themselves at the expense of publicly-funded research institutions.

Impeach them.